The teaching artists at Snow City Arts have a saying, “Choice is voice.”

The children they work with don’t have much say about what happens throughout their time in the hospital. Tests, treatments, doctor visits, meals, mobility: these decisions are made by the medical staff.

So from the first thing the teaching artists say when they poke their head in the door—“Would you like to make art today?”—the artists prioritize the student’s autonomy and respect their space. If they choose to work with an teaching artist, they choose the subject matter, the type of art, the materials, everything.

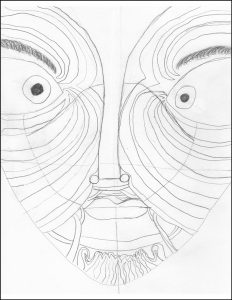

Not every student, however, has an art project in mind. About half the time, they’re open to participating in a planned project. Students will often be interested in drawing a face, usually their mom, their self-portrait, or someone they know. For these moments, teaching artist Allison Spicer created the Picasso project, one of a set of guidelines that SCA artists have designed to give students an opportunity to be creative while learning new techniques, art theory and art history, too.

“It is really difficult to jump to drawing faces without any knowledge of drawing techniques,” Spicer says. “So I came up with the Picasso project that deconstructs portrait drawing into symmetry, contours, shapes, forms, proportions, and color.”

Spicer first offers portraits by Picasso as a reference, and the students use known shapes like circles, lemons, triangles, and letters to deconstruct facial features. They learn about portraiture, color, and abstraction, and how to represent different angles and perspectives.

Even within the structure of the project, students still direct the artistic experience. Spicer talks about how 10-year-old Eduardo wasn’t interested in color—but he did see how the shapes and forms he created could be spaces for marks and lines of repetition. Thirteen-year-old Citlalli chose to add some gray into her artwork, wanting the colors to “pop” instead of competing with each other.

Spicer finds out what medium the student is interested in using—pencil, watercolor, oils, mixed media—and she takes into account issues specific to the hospital environment, like if the student has access to both hands or can sit up to work. If she stops by the hospital room the next week and the same student is available, they can build on what they learned for a new project. Some students, especially the younger ones, prefer to try another Cubist portrait, while some don’t fully remember the last session due to medications for their treatment. “You have to constantly assess, be flexible, and think on your feet to engage the student at that particular moment,” Spicer admits.

For the 60 to 90 minutes that Spicer typically works with a student, he or she can forget about their medical problems, and concentrate on how to use the pen, pencil, brush, or stylus to make their vision a reality. Spicer told us a recent story about a 6 year old girl who began to tear-up when a staff person from the hospital came in and told her she was discharged.

“She wanted to stay and finish her artwork. ‘Just five more minutes,’ she said, even though she’d been in the hospital for days,” Spicer says. “It’s a truly unique teaching job, and I feel very fortunate to do this work.”

Thanks, great article.